A View of the Imperium (From a Bridge Down Under)

Random Reflections on the Grand American Narrative

A View 👀of the Imperium (From a Bridge Down Under), by Greg Maybury

Hello Friends,

Following on from last week’s posting titled—“The Prophet of the Chilled Delirium — Inside James Jesus Angleton's Wilderness of Smoke n' Mirrors”—I’m in the process of retrieving from my personal Memory Hole (yes, I have one too), a slew of largely unpublished writings I penned back in the day when I first began reflecting on the Grand American Narrative. For better or worse, these ruminations (which cover a lot of real estate), run the gamut from the serious, the whimsical, the sardonic, the contemplative, the sober, on to the satirical, and perhaps a few more points in between. |—|

The following is an update of one rumination from over ten years ago when I first began to write about America, its history, its place in the world, and where it might be heading. This has remained unpublished since that time. Some minor editing for clarity and context was necessary. But for the most part the original narrative remains intact. It may be of interest to some of my Stateside confreres, and even a few others. Feel free to circulate, repost, and republish as you see fit. Stay tuned for more. If you’re up to the challenge. GM.

— America Then and Now

When I first began to write in this vein, it was with a pronounced feeling that there was something decidedly rotten with the State of the Union, and I ain’t talking about the annual presidential address to Congress. As I found out, I didn’t have to look too hard for confirmation that such feelings might be justified.

Yet at the same time I felt that possibly, just possibly, there may be some collective redemption to be had if Americans recognized that their real enemies (then and now) aren’t and weren’t who they thought they were. Perhaps the real enemies were much closer to home.

Moreover, the Great Promise of America as it has been portrayed relentlessly and unabashedly throughout my lifetime was much easier to accept when I was younger. However—for both America and myself it would seem, in a relatively short period of time, that “Great Promise” has morphed seemingly inexorably into something less than the sum of its well publicised parts.

And it has to be said, the greater the promise, the greater the threat if and when that promise is not realized. The characteristically acerbic H L Mencken—the ‘Sage of Baltimore’ and one of America’s most insightful commentators, writers, journalists, and essayists of his era—perhaps said it best; and indeed the following succinctly sums up the ‘we have met the enemy’ notion:

“The whole aim of practical politics is to keep the populace alarmed—and hence clamorous to be led to safety—by menacing it with an endless series of hobgoblins, all of them imaginary.”

Readers should appreciate that this is not an attempt to denigrate America, or write its epitaph. It is at once a lament, and a heartfelt attempt to present an alternative view of the US—albeit one dripping with no small measure of irony—than the one with which we are most often presented. Then and now.

As a young kid growing up in semi-rural Australia in the fifties and sixties, it was inconceivable that one might even contemplate such notions much less express them like I’ve attempted to do herein. Like possibly many other Australians young(er) and old(er)—and I suspect, other non-Americans—I was enamoured, entranced and enthralled by most things American. Whether it be its music, its film, its literature, its art, its (‘high’ and ‘low’) culture, its national affairs, history, its ‘by-the-people, for-the-people, of-the-people’ system of government and philosophy of governance, its myths and legends and fabled constructs, and even its dream-sequenced democracy and ‘self-evident’ ideals of freedom and notions of egalitarianism. It was all up for grabs! I couldn’t get enough of it.

Moreover, like many folk I still believe in the “ideals” and “constructs” of a true democracy espoused if not always reflected by the American experiment, or indeed, practiced by those ‘conducting’ said “experiment”. To the extent moreover that at such a young age one could grasp the intricacies of politics and nuances of history and the interconnections between them, what they mean, and how both form such an important part of our lives, it was probably American politics and its history that I took more of an interest than that of my own country.

I was though vaguely aware that there was something seriously amiss when the Americans invaded Cuba at the Bay of Pigs in 1961. The following year I recall for instance agonizing over how the Cuban Missile Crisis (CMC) would play out, as even at ten years of age I at least had some idea of the implications for the world and humanity if America and the USSR did not succeed in their attempts to resolve the crisis. (I’d seen photo and film footage of the aftermath of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, absorbed the statistics, and read the ‘fine print’. The implications of a nuclear war between the US and the Soviets was a no-brainer then, and still is!)

Of course it wasn’t until some time later that I realized how much the political and later on, economic, destinies of both our countries were intertwined, and moreover, how much we have been impacted and influenced for better or worse by American social and cultural memes. Again, for better or worse.

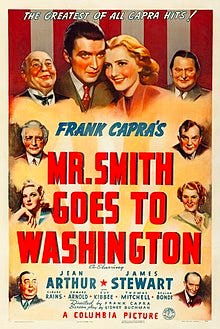

Apart from the films of Charlie Chaplin, the Marx Brothers, and Laurel and Hardy and their ilk, of the more serious, memorable fare I watched as a youngster was High Noon with Gary Cooper, Casablanca with ‘Humpy’ Bogart, Brando in On the Waterfront, and Mr Smith Goes to Washington starring Jimmy Stewart (America’s then resident “Everyman”). Of course this latter film seemed to me then a great homage to:

a) the promise and potential of the American brand of democracy;

b) the egalitarian ideals of the Home of the Brave and the Land of the Free; and

c) the ‘inevitable’ triumph of the many less/least powerful over the few more/most powerful.

That it resonated with my own nascent impressions of the country was also something I recall well. Although I may not have realised it as such at the time, it was nonetheless a powerful reinforcement of the notion of ‘the good will out’—the idea that decency, justice, fairness and integrity in public life ‘inevitably’ prevails over greed, corruption, arrogance, duplicity, oppression, ignorance, and self interest, for the betterment of the greater good. Indeed, I felt somewhat proud that my own country saw fit to closely identify with the US insofar as we shared similar values, aspirations, ideals and attitudes toward the grand polity. These Americans were (the) good guys! Of this there could be no doubt! (The realisation that it was all an essentially illusory construct came much later.)

Yet, on a very different plane, I was also, even then, somewhat ‘obsessed’ by the Dark Side—what I refer to as the history noir—of this strange yet compelling land of contradictions, conundrums and confounding conflict. After years of taking in the story (from books, TV shows, music, films etc.), of the Great American Triumph that was the opening up of the Old West and the accompanying sacrifice, heartbreak, tragedy, and supreme hardships of the early settlers, I recall being mightily taken with the mythology of the Western Frontier. (Richard Slotkin’s trilogy here is essential reading.)

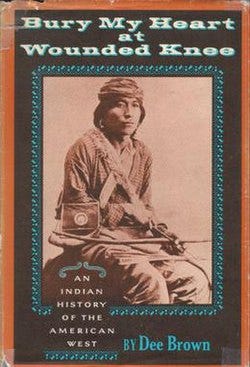

That was until I read Dee Brown’s seminal Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, a brutally unsentimental debunking of this “triumph” and a no-holds-barred expose of the despair, bitterness and utter tragedy of the folks who paid the biggest price for the ‘winning of the West’, with sometimes much less deserving, less decent folks and their descendants benefitting the most.

By any measure Brown’s book is one of the most disturbing accounts of the displacement, brutal oppression and then ultimate decimation of a native population out there in the annals of human history. It is made all the more disturbing by the economic success and the geopolitical primacy the country achieved as a consequence of that displacement, of which little has been of much benefit to the remaining ancestors. (For the record, Australia’s own history in regard to our treatment of the indigenous peoples has been far from exemplary.)

Then of course there is the plight of African-Americans, whose story I also became very familiar with at a young age. Their music in particular—from the early spirituals, to gospel, jazz, blues, soul and hip-hop—has had a profound impact on my life, and continues to do so. Their battle for civil rights—indeed, for human rights—is one of history’s most epic, most inspiring struggles. And in socio-economic terms especially, it is incomprehensibly, a battle still raging. (The work of James Baldwin was of particular interest at the time, though it took some years for me to better appreciate exactly where he was coming from.)

SIDEBAR: I always marvelled at the supreme irony of a bunch of Limey council estate refugees, bored middle class teenagers and art-school dropouts from across the Pond (The Beatles, Rolling Stones, The Who, The Animals, The Kinks, The Yardbirds, Fleetwood Mac, Led Zeppelin et. al) and the like who were able to take America’s own music, reinvent it and then sell it back to them. This is an outcome for which all lovers of great contemporary popular music should be forever grateful. This irony is all the more profound given America’s propensity for exporting its culture via the mediums of film, literature, television, fashion, language etc. to the extent that it is often accused of cultural colonialism as well as some of the more recognizable forms.

And it is an outcome that the African-Americans themselves who created the blues and inspired its development in the first place, by most accounts and for the most part, have been appreciative of. This, even if it didn’t always translate to the monetary reward that might otherwise have been their due. At least for a few of them, it helped revive dormant careers and enabled them to make a decent living, with the added benefit that they would not die in complete poverty and obscurity. Sadly though, so many did. The legacy they left behind though is indelible, their music incomparable.

At all events, White America’s treatment of the folks who were once their slaves even a century and a half after the end of the Civil War—a war that cost the lives of over 600,000 Americans and the life of a president, and which was ostensibly (i.e. allegedly) fought to end not just slavery but pave the way for the elevation of black folks to the status of the white person as per the Constitution and the Bill of Rights—arguably remains the biggest blot on the landscape of the American narrative.

Moreover, the assassination of Martin Luther King—iconic leader of the black civil rights movement throughout the fifties and sixties—along with that of Malcolm X, another equally iconic black leader of the era—are stories that, like JFK’s, will probably never be told in their entirety for the very simple reason that a lot of folks with vested interests did not want them told. (See here and here.)

That America blithely and meekly ‘accepted’ the official story behind these events is a ferocious indictment on the country and the folks that populate it. Even now, there are some extremely serious minded people who would prefer that these “stories” never see the light of day. Because if they did, America’s own ‘light’ might be somewhat diminished. (It’s here that George Orwell’s indelible adage from 1984—‘He who controls the past, controls the future’—comes to the fore.)

Further signs of this uniquely American Dark Side were no less evidenced than by the gangster era that rose to prominence after the passing of the infamous Volstead Act in 1919 and which ushered in the Prohibition period. Aided and abetted by FBI Director J Edgar Hoover’s persistent, decades long denial that such an organization even existed, this development facilitated the uninhibited growth of the Mafia to gain a stranglehold on US society, culture and politics, and indeed, the economy. It was for decades to come to have a deeply corrosive, long lasting impact on the workings of the American democratic ideal at every level in general.

That notionally perverse fascination with the darker, ‘noirish’ corners of the much espoused and preposterously mythologised American Dreamscape was shaped later on even further by books as diverse as Henry Miller’s The Air Conditioned Nightmare; Joseph Heller’s Catch-22; JD Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye; John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath and Of Mice and Men; F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby; Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, and Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. There were also plays such as Arthur Miller’s View from a Bridge and Death of a Salesman; Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolff; and Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire.

Then there was music from Billie Holiday’s Strange Fruit, Woody Guthrie’s Vigilante Man to Bob Dylan’s Masters of War and [the] Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll, along with a diverse ‘offering’ of films such as Arthur Penn’s Little Big Man, Stanley Kubrick’s Dr Strangelove, Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now and The Godfather (1 & 2); Bernado Bertolucci’s Once Upon a Time in America; Michael Cimino’s Deer Hunter; Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets and Taxi Driver; and John Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate.

In addition, there was of course the hardboiled ‘melodrama’ of classic film noir (with examples too numerous to mention), which in itself hinted at a degree of collective self-awareness upon the part of some Americans that their so-called American Dream had its schizophrenic side, its own collective personality disorder.

Fortunately, not everyone was drinking the seemingly ubiquitous, free-flowing Kool-Aid!

That said, it is important for American readers to understand Australia’s—and I suspect those of other Western nations not dissimilar to our own—‘love/hate’ relationship with the United States. For us one of the most important events in the development of our close ties with the US occurred at the Battle of the Coral Sea (BCS) in May 1942, something of a watershed moment for Australia’s bi-lateral relationship with the US. It was after this event that we began transferring our allegiances from Britain to the US, one that resulted in the signing of the ANZUS treaty in 1951 with America and our own close neighbours New Zealand; the treaty is still a bedrock—for better or worse—of our compact with Uncle Sam.

The BCS itself would prove to be a strategic victory for the Allies, with Japanese expansion, seemingly unstoppable until then, being turned back, and preventing ultimately an invasion of Australia. And in response to the BCS and the successful defeat of Japan in the Pacific, it is sometimes jokingly said that if it weren’t for the Americans, we’d all have ended up packing sushi in our kids’ lunchboxes and ‘saluting’ the Rising Sun instead of the Southern Cross during school assembly!

Put simply, Americans had ‘saved’ our collective asses by helping us to defeat the Japanese in this pivotal theatre of the War, the biggest existential threat to our way of life up until that point. Yet on the other hand, American servicemen based in Australia throughout the war caused a lot of friction with Aussie blokes in particular, who saw them as being “overpaid, over-sexed, and over-here”. And we ‘enjoy’ the (many would and do say, highly dubious) distinction of having unquestioningly supported the United States in every war it has embarked on since that time, including most recently in Iraq and Afghanistan.

On a different tangent, I remember particularly well taking an interest in a young, up and coming Senator from Massachusetts, one John Fitzgerald Kennedy (JFK), who looked and acted unlike other politicians of the era. His election to the presidency in 1960 I recall being more than just vaguely aware of—especially his “the torch has been passed to a new generation” inauguration speech in 1961. This seemed like in some ways he was speaking to me, and he wasn’t even my president. I am sure many non-Americans possibly reacted the same way.

Although only about eight at the time, clearly even then I was in the process of developing a degree of political awareness and an abiding curiosity about history (and eventually the requisite connections between the two), and at least a sense of the message he was trying to impart to his fellow Americans and the ROW, and what it might mean. The clarity of his message has only become sharper with age.

And of course in November 1963, like almost everyone else on the planet in close proximity to another sentient, bi-pedal carbon based life form or a radio, I heard the news! JFK was dead! Shot down like a rabid dog in the street. This, even then, appeared to me to be a “game-changer” (or whatever phrase back then that might’ve encapsulated the same idea). Like millions of my fellow countrymen and women, I was deeply shocked, disturbed and unnerved by the Big Event.

To be sure then the JFK assassination was one big-ass History Mo’, and one which I’ve spent many years on and off trying to make sense of. From that time onwards I never viewed America in quite the same light again. A similar reaction greeted me on September 11, 2001. But I’ve never really stopped looking either, ie. trying to make sense of it all. My ongoing writing efforts—although belated—are an attempt to make sense of a country and its role in the world today. Of course this is an impossible, unrealistic endeavour, as making sense of America at best is a never-ending work-in-progress. It is not without its compensations though.

But it seems to me that without a “New Torch” and a whole new way of thinking by a “New Generation” of folk that the days of the Empire—much like JFK’s were in June 1963—are numbered. The American Empire is—to use the popular vernacular—unsustainable if it persists down the path it is heading.

Far from being the “indispensable nation”, it will sooner rather than later, be seen as the eminently dispensable, perhaps even now, disposable nation. A former shell of its not so exceptional self then? In many corners of the world, America is already there.

We Have Met the Enemy, and He is US! Indeed, ‘he’ is!

Greg Maybury, 2012-2022.

See Below for More:

The No Fly Zone with Greg Maybury

EACH SATURDAY: 6PM-7PM — BRISBANE) | 9AM-10AM — LONDON) | 3AM-4AM — NEW YORK) |

The No Fly Zone on Australia’s TNT Radio is a weekly one hour program by Greg Maybury.

Greg seeks via brief op-ed and extended interviews with prominent authors, analysts and commentators to explore deeper aspects of the latest news, covering geopolitics, world history, Western foreign policy, media ethics, propaganda, censorship, the national security state, globalism, and the broad political economy.

In the true spirit of alternative/independent media, of particular interest will be those topics, themes and viewpoints which the establishment media have effectively declared “No Fly Zones”.

https://tntradio.live/shows/the-no-fly-zone-with-greg-maybury/

https://tntradio.live/presenters/greg-maybury/

email: gregmaybury@protonmail.com

substack url: gregmaybury.substack.com

substack email: gregmaybury@substack.com

"denigrate America"? America deserves all the blackening of reputation the truth can expose:

Another Aussie writer has shown just how black the USA is, in one short paragraph:

"In my lifetime, the United States has overthrown or attempted to overthrow more than

50 governments, mostly democracies. It has interfered in democratic elections in 30

countries. It has dropped bombs on the people of 30 countries, most of them poor and

defenceless. It has attempted to murder the leaders of 50 countries. It has fought to

suppress liberation movements in 20 countries."

- John Pilger - "Silencing the Lambs, How Propaganda Works" at Consortium News

The only limitation I would agree to is that America's reputation is due to the games of the rich far more than the blind participation of the rest of the population.

I used the example so as to show, in a more direct way, that whether Bernays was a jolly good fellow or a reprehensible cad has little or no bearing on who is to blame for the current state of affairs. As for wellbeing for all, I side with Lao Tzu in seeing that is simply not in the nature of things. Trivially, if all suffering were somehow eliminated, then the least happy among the survivors would then be the sufferers! Our exchange of ideas here much enjoyed!